The ultimate guide to what floats your boat

Andy King, naval architect and director of stability & statutory for Houlder Ltd, sets out the key considerations that yachts must comply with to keep safe…

It’s widely recognised that the two biggest risks to any yacht are from fire and flood. There has been an increased industry focus and publicity on fires from the likes of Lithium-Ion batteries. This year, we’ve witnessed a number of incidents involving yachts suffering damage or taking on water, the most high-profile being the tragic sinking of Bayesian in a storm in August, which killed seven of the 22 on board.

But such incidents only concern yachts when they have been evidently damaged, taken on water or have been unfortunately lost. However, a yacht which is afloat needs to always have adequate stability, whether it’s damaged or intact, crossing the Atlantic or moored with its stern door open. Indeed, a yacht will always have certain stability characteristics. Just standing quayside at the recent Monaco Yacht Show, in a sheltered harbour and with minimal wind, it was very easy to see how some yachts were more susceptible to movement and motions than others of comparable size and shape.

The stability of a yacht can be a difficult concept to understand, measure, monitor and predict. We’re dealing with some crucial numbers; the weight of the yacht (its lightweight), the weight of everything loaded on board (its deadweight), the overall vertical centre of gravity and then abstract concepts such as the yacht’s metacentre. These values or points can’t be seen, can’t easily have a ruler put down alongside to measure them and they are all susceptible to change.

It’s fundamental to get a good understanding of a yacht’s stability and to ensure that it remains compliant with the required criteria. These complex and changing parameters ensure that understanding the stability of a yacht is a technical and operational challenge.

Below is an overview of stability and what a yacht must comply with. It will detail what a Stability Information Booklet is and why it’s important for a yacht. It will also discuss some of the common stability challenges for yachts.

Stability: A brief reminder

At this stage it’s worth thinking about the key question: What is stability? Put simply, the stability of any yacht is a measure of how easily it returns to the upright. If the yacht heels over due to a movement of a weight on board or from an external force such as wind or a wave, how does the yacht behave, how quickly does it return to the upright position and what kind of righting energy does it have?

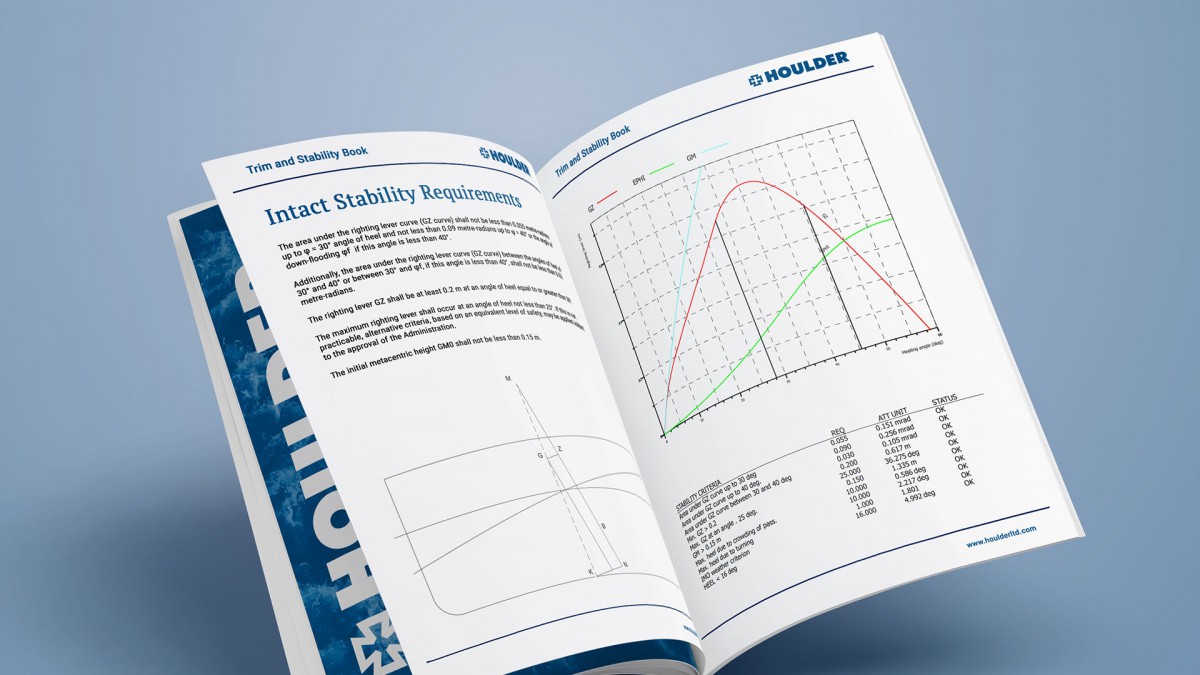

This is called the yacht’s intact stability – how it behaves from a stability point of view when the yacht is intact and complete. The yacht will also have a damage stability behaviour, and this is based on what floating position (heel, trim and sinkage) it will adopt when subjected to a given damage. For both intact stability and damage stability, there are prescriptive criteria which a yacht must achieve to be deemed compliant.

In defining the term ‘stability’ and what a yacht must comply with in terms of criteria, it’s important to draw a distinction between static stability and dynamic stability. The yacht’s static stability will determine its compliance with the required criteria and the yacht’s ability to stay upright and withstand damage. The yacht’s dynamic stability will determine how it behaves in waves and its overall motions. This can often cause confusion in the yachting industry when designing a vessel for comfort with respect to motions and rolling.

There’s a complex set of technical considerations to think about when designing or maintaining a yacht to have compliant static stability as well as having motions acceptable to those on board. If a vessel has a centre of gravity that is too low, the yacht can end up slowly rolling, whereas if the centre of gravity is too high, the yacht can be very stiff and have high accelerations. While bearing this dynamic aspect in mind, we’ll focus purely on static stability and the required criteria.

It’s worth noting that the required stability criteria represent a minimum standard that must be met. There’s nothing to stop a new-build yacht being designed to meet a higher stability requirement, although there’s obviously a cost and design implication to be considered alongside this.

What stability does my yacht require?

The three big factors which affect what a yacht must comply with from a stability point of view are the Flag administration, registration and operation. Stability criteria are a statutory matter which means that they are defined and applied by the yacht’s Flag administration. Linked to this is the yacht’s registration and whether it is commercially registered and operating on charters or privately registered.

The operation of the yacht is also fundamental in terms of whether it is restricted in terms of range. These three factors should always be carefully considered when it comes to understanding the way

in which intact and damage stability criteria are applied and complied with. If there’s any question, it’s always worth discussing with the Flag administration or classification society of the yacht in question.

At this point it’s important to explore further the distinction in stability criteria requirements between privately and commercially registered yachts. A commercially registered yacht must comply with the applicable stability criteria as set out in the relevant code from the Flag administration. For a privately registered yacht which is registered with a classification society, the application of stability criteria becomes a Class matter, and it’s often the case that intact stability, a possible range restriction and an approved Stability Information Booklet is still required. It’s important to remember that, whether privately or commercially registered, the physics and safety critical nature of stability for a yacht remain the same.

It’s also worth noting that the required stability criteria represent a minimum standard that must be met. There’s nothing to stop a new-build yacht being designed to meet a higher stability requirement, although there’s obviously a cost and design implication to be considered alongside this. This exceedance of the stability requirements may come in the form of a privately registered yacht opting to comply with damage stability requirements or by exceeding the criteria values through larger compliance margins.

The Stability Information Booklet – what’s in it and why is it important?

In almost all cases, a yacht will be required to have a Stability Information Booklet. This is a fundamental document for the yacht and will set out everything related to the stability and loading of the yacht. The Stability Information Booklet will be developed during the build of a new yacht and will often be one of the last documents to be finalised owing to the nature of some of the information it contains that can only be known when the yacht is complete. The Stability Information Booklet will then be kept on board and will be updated as required throughout the life of the yacht. It will be an important document for outlining restrictions in the event of a survey or resale of a yacht.

It’s important to point out that the title of the document is key; it’s a booklet containing all stability information relating to that yacht. There’s no such thing as an intact stability booklet or a damage stability booklet. The yacht may have a separate and supporting damage calculations booklet, containing reams of numbers and results, but the Stability Information Booklet is the overarching document and can be read and understood on its own.

The Stability Information Booklet should be kept on board and, as well as a lot of technical details about the yacht, will detail some key information. Perhaps the five most important pieces of information about the yacht are its lightweight, maximum draught, loading conditions, openings and limiting stability information.

The lightweight of the yacht will define the weight and centroid with absolutely nothing on board. This is determined at build by an inclining experiment and is crucially monitored throughout the life of a yacht by a lightweight survey; either every five years or after a major refit.

The maximum draught of the yacht will define the maximum floating position for the vessel; it may be limited by design, by the structure, by hull openings, or by some other statutory aspect.

The loading conditions of the yacht will document the way in which it is loaded when full of fuel, fresh water, guests and stores and how it is loaded when it is at its lightest. The former is called the departure loading condition and the latter is called the arrival loading condition. The loading conditions will set out how tanks and items on board are loaded and will set out how the loading of the yacht changes from departure to arrival.

In this sense, it’s important to note that these are statutory loading conditions and may not represent operational loading conditions. These additional operational loading conditions may still be included in the Stability Information Booklet and are always useful to have as a reference for those on board and ashore.

The internal and external openings on the yacht will be set out in the Stability Information Booklet. This will include interior doors and hatches and their watertight integrity which are designed to stop progressive flooding between internal compartments. The list will also include the external openings which will define where and how they are open. The openings could be always open (such as an engine-room vent) or they could be a weathertight door or hatch.

The way in which these openings are considered and treated in stability calculations can be very technical but the important point to understand is that a critical opening may terminate the stability of the yacht. This means that there may be an opening which, when immersed, causes what is called downflooding – this is crucially different from the angle of vanishing stability. It’s important to note that the downflooding angle can occur at a much earlier heeling angle than the angle of vanishing stability.

The fact that a yacht changes throughout its life is perhaps difficult to fathom. Even if

the ownership doesn’t change and no substantial modifications are made to the yacht, it’s common

to find that the lightweight and vertical centre of gravity tend to increase over time. In fact,

this is common for all vessels.

The yacht’s limiting stability information will often be displayed as a set of curves called the Maximum Vertical Centre of Gravity (VCG or often referred to as KG) curves. These curves will define, for a given draught or displacement, the maximum vertical centre of gravity (adjusted for fluids on board) that a loading condition can have before the condition is shown to fail the stability criteria. It’s worth noting that there’s a naval architectural peculiarity in that a loading condition may sit above the maximum vertical centre of gravity, so would be shown to fail the stability criteria, but would be found to comply with the stability criteria by direct calculation.

If there’s ever a question over the content of a Stability Information Booklet always ensure to consult a qualified and experienced naval architect, your Flag administration or Classification society.

Does the Stability Information Booklet match the yacht?

This is a critical question when assessing the stability behaviour of a yacht. The yacht may change through its life and therefore it’s important to understand if the Stability Information Booklet accurately reflects the current use and physical condition of the yacht. For example, is the yacht loaded as shown in the Stability Information Booklet? Are the yacht’s openings accurately recorded for location and closures? Does the yacht have a pool which is empty in the Stability Information Booklet and full in practice? Does the yacht use a helicopter which is not featured in the Stability Information Booklet? All these questions are key to get right.

The fact that a yacht changes throughout its life is perhaps difficult to fathom. Even if the ownership doesn’t change and no substantial modifications are made to the yacht, it’s common to find that the lightweight and vertical centre of gravity tend to increase over time. In fact, this is common for all vessels. Equipment, spares and minor things are brought on board, items get squirrelled away in voids, changes may be done that are not recorded; all these actions may be minor in isolation but come together to mean that the yacht is changing.

This is normally captured every five years when a yacht will be subjected to a lightweight survey. The lightweight survey will inform the captain and management company about the change in the lightweight and the longitudinal centre of gravity (affecting how the yacht trims forward and aft in the water). It will then be compared against limits to determine if the yacht needs to have an inclining experiment.

An inclining experiment is a key event for any yacht. It’s a practical measurement on board that will determine the yacht’s lightweight, longitudinal centre of gravity and vertical centre of gravity. It will mean that the yacht will have a new Stability Information Booklet, superseding everything that has come before and therefore it always brings the stability assessment for the yacht up to date.

There was a recent revision to the Red Ensign Group Yacht Code Part A including the requirement to explicitly consider the impact on stability when opening hull doors and having low sill heights. There’s a clear design and aesthetic quality to having openings that are close to the waterline but this also comes with important technical considerations.

Common yacht stability challenges

It’s useful to share and discuss some of the common challenges which cause issues for yacht stability. The challenges and scenarios that may need special stability consideration are numerous and complex but, here, we’ll present and discuss some of the most common ones.

Growth: By far the most common challenge is related to the last section – specifically, whether the Stability Information Booklet matches the yacht and the weight growth of the yacht. This challenge may present itself in one of two ways: either the new-build yacht doesn’t accurately reflect the as-built inclining experiment or the yacht has experienced weight growth through its life.

For example, for the first issue, maybe the as-built inclining experiment was conducted too early and then, at the first five-year lightweight survey, the yacht is found to be over the allowable lightweight tolerances without any modifications having taken place. If the yacht has experienced weight growth through its life, then both issues will mean that a complete recalculation and reapproval of the stability of the yacht is required.

Stability margins: The big challenge with growth then comes if the yacht, upon recalculation, can’t comply with the applicable stability criteria. For some yachts, this can become a significant problem that impacts operation and future capability. In the most impactful way, a yacht may have gained weight and therefore can’t load all its deadweight without loading deeper than its maximum draught. This means that the yacht is restricted in terms of deadweight in its deepest condition. Then, in reverse, it may also be restricted in its lightest condition; this is when the stability of a yacht is usually most onerous from a vertical centre-of-gravity point of view and perhaps some deadweight is needed to be retained to keep the centre of gravity down.

These two issues can manifest themselves in the following scenario: Imagine a yacht which can’t load all its tanks in its deepest condition and can’t empty all its tanks in its lightest condition. The net result is an operational impact on range. There are ways around this but it requires careful and bespoke technical consideration from a naval architect. Possible options may be loading to a deeper draught (if this is possible from a structural and load line point of view), carefully reanalysing the stability approval, fitting solid ballast, or physical geometry changes such as a larger swimming platform which can greatly improve stability.

A yacht will be able to withstand gains in weight and centre of gravity if there is adequate growth and stability margin in the original Stability Information Booklet. The growth margin can be included upon delivery to account for the inevitable through-life growth that we’ve discussed. The stability margin can be included by ensuring that, upon delivery, the yacht doesn’t have loading conditions that are tightly pressed up against the maximum VCG curves.

Hull doors and sill heights: There was a recent revision to the Red Ensign Group Yacht Code Part A and this included several updates to the stability requirements, some of which are still being debated. Perhaps the most significant was the requirement to explicitly consider the impact on stability when opening hull doors and having low sill heights. There’s a clear design and aesthetic quality to having openings that are close to the waterline but this also comes with important technical considerations.

The stability of a yacht in the approved Stability Information Booklet relates to how the vessel is

loaded in what are called seagoing loading conditions, that is the scenario when the yacht is closed up, secured for sea and able to transit between locations. There’s a significant period of a yacht’s life when it is secured and floating, perhaps with doors open and therefore not in a seagoing loading condition mode. It’s this scenario the new requirements aim to capture: analysing and assessing, for a given sill height, what may happen to the yacht if a layer of water enters the internal space – for example, the beach club or tender

garage.

The industry should be pushing for yacht designs and operations that are compliant by design at all times– i.e. adequate and compliant stability is achieved without active intervention which may be operationally missed, forgotten or fail.

It’s evidently beneficial that if this happens, the yacht is able to survive the flooding and subsequently deal with it through closing hull doors, draining or pumping flood water and, critically, not allowing the flooding to spread to other compartments.

Staying compliant at all times: There’s a useful question to consider in yacht stability; can my yacht go from its deepest condition to its lightest condition in a compliant manner? The answer to this is in the Stability Information Booklet. The common challenge here comes when compliance can be achieved only by active management of weights on board and this is generally not permitted. For example, if tanks are shown to be used as effectively water ballast tanks or whether active systems such as watermakers are relied upon to be doing the same.

In all these ‘active-management’ cases, the industry should be pushing for yacht designs and operations that are compliant by design at all times– i.e. adequate and compliant stability is achieved without active intervention which may be operationally missed, forgotten or fail.

Similarly, does the yacht comply in the event of damage? For example, does a pool need to be dumped, are internal downflooding devices needed to be active, are tanks needed to correct heel angles? Again, all these active actions are things that we should avoid to ensure a yacht is operating well from a stability point of view.

Special operations: The last common challenge that we’ll discuss are the scenarios when the yacht is doing something different. For example, we’re thinking about the times when the vessel may be using a helicopter, launching a tender, hosting a party or even using the pool. All these scenarios will have a significant impact on the stability of the yacht and should be things that need to be considered and checked.

Think about the simple act of filling the pool; the yacht needs to move weight to a (generally) higher location and the pool will have what is called a free surface effect. This effect is crucial and reflects the ability of the surface of the pool water to move about. It will have a measurable effect on the stability of the yacht. As well as heeling due to launching a tender or having the additional weight, albeit temporary, of a helicopter on board, all these aspects need to be thought about carefully.

Conclusion – yacht stability always matters

There have been so many news articles in the yacht industry of late relating to stability incidents, so it’s important that all stakeholders keep a keen eye on the stability of their yachts. It’s highly recommended to have a review of the Stability Information Booklet for your yacht, understand how and when it was approved and to determine if it accurately reflects the yacht as it’s operating today.

Stability should not be something that is approved upon delivery of a new-build yacht and never considered again. It should be actively managed and monitored throughout the life and operation of the yacht. As we’ve said above, if you have a question or concern relating to your yacht then it’s always best to contact a naval architect, your Classification society or Flag administration.

This article first appeared in The Superyacht Report – Refit Focus. With our open-source policy, it is available to all for a limited period by following this link, so read and download the latest issue and any of the previous issues in our library. Look out for the New Build issue coming in February!

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

Atina sinks in Sardinia

The 47-metre Heesen was engulfed in a blaze that reportedly started in the tender garage

Fleet

Fire erupts at Sirena Yachts shipyard

Yet another blaze has been reported at a superyacht shipyard, this time in Bursa, Türkiye

Crew

Flagging the Fleet – convenient or inconvenient?

Choosing which Flag to build and operate your superyacht under is an important decision and has consequences and impacts if you don’t do your homework

Crew

Dubai Marina clear after unprecedented storm

Dubai Marina is now clear, while the UAE government has advised all citizens to remain at home during its most significant rain storm on record

Fleet

Cracking the Code

The REG Large Yacht Code forms the foundation of safe construction in the new-build sector. Here, we look at the 2024 revisions

Crew

Related news

Lessons from nature

1 year ago

Atina sinks in Sardinia

1 year ago

Fire erupts at Sirena Yachts shipyard

1 year ago

Flagging the Fleet – convenient or inconvenient?

2 years ago

Dubai Marina clear after unprecedented storm

2 years ago

Cracking the Code

2 years ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek