The value of class: behaviour-based safety

Part of an interview series with its experts, Lloyd's Register assesses how human factors can impact on-board safety…

While increased regulations and evolving technology are both key factors that contribute to improved maritime safety, the design of systems and technology for the human operator are still found to be the root cause of many maritime incidents. As such, behaviour-based safety is a valuable process that can significantly improve a vessel’s safety performance by changing the way that people behave on board. In the third instalment of a series of interviews with Lloyd’s Register experts, Thomas Zeferer, Manager of Marine Training Services for Northern Europe, and Engel-Jan de Boer, Yacht Segment Manager, discuss building a culture of behaviour-based safety in the superyacht industry.

Firstly, a culture of behaviour-based safety must start from the top – at the manager and captain level – and then filter down to the guests. “The number one priority of any yacht should be to provide a quality service, but with safety being one of the most dominant values,” Zeferer explains. “Safety means a lot of different things to different people, so translating that value into actual behaviour starts with setting the right example. On a yacht, that means providing quality service but also telling guests when they are doing something that is fundamentally unsafe or not in their best interests.”

A culture of behaviour-based safety is especially important on superyachts where safety can often be taken for granted, particularly by those who are enjoying the luxury on board. “Superyacht crew are generally focused on the entertainment of guests, but we should never forget that those guests can only enjoy the luxury because of safety, and that shouldn’t be hidden away from the entertainment,” adds de Boer. “As soon as anyone comes on board, they should be familiarised and made aware that it can potentially be a dangerous environment. If the crew can demonstrate that, it’s their behaviour that will influence the behaviour of others on board.”

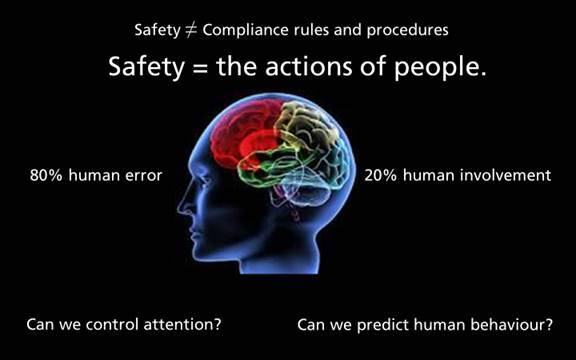

As behaviour-based safety involves a systemic application of psychological research on human behaviour to the issues of safety in the workplace, another important aspect that needs to be considered in relation to the topic is how a yacht prescribes its crew carry out on-board procedures. While there’s always an urge to overcompensate and provide stringent controls and checklists for each operational procedure, the principles of behaviour-based safety dictate that this can be counterproductive.

“It’s quite possible to follow a procedural checklist exactly and still end up in a dangerous situation,” advises Zeferer. “Because if you have too many controls, it takes something away from someone’s awareness. A competent seafarer that has been well trained and has an acute grasp of the context that he or she is operating in doesn’t need to be provided with the same level of checklists or controls. It’s more important to trust the crew and empower them to do what they need to do based on the competencies that they have, while maintaining the prescriptive controls and details that were necessary (for example, where a procedural requirement can be explained in various ways).”

While it can be a challenge to achieve the right safety balance between best practice and giving the crew responsibility, if a yacht needs to have stringent checklists and procedures in place to achieve something, it might be an indication that something is lacking with the interface between the humans and machines on board. This is where human-centred design also comes into play – the operation of equipment should be intuitive and easy, starting from the design.

When accidents do happen, however, incident analysis is another key factor. By learning from incidents and designing intuitive systems that fit the process, people are put in the best possible position to do the right thing. De Boer argues that if the superyacht industry would be more transparent and willing to share incidents and the lessons learned, it would greatly promote and improve the safety record of the industry. “The accidents that do get reported are usually those investigated by the flag states, which means that a serious accident has taken place, and that's too late,” he cautions. “There needs to be more emphasis on not just the big disasters but the near misses and learning from them as well.”

While classification societies are typically known for creating technical rules and regulations in the maritime industry, their focus on human factor aspects through human-machine interface services and on-board safety culture and leadership assessments is often overlooked. But Lloyd’s Register sees this as one of its most important roles. As de Boer concludes, “We can gain more in terms of safety and quality by looking at human factors than by just increasing the number of regulations with respect to technical requirements”.

Profile links

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek