Refitting for the inevitable future

Feadship’s Pier Posthuma de Boer and Giedo Loeff discuss the pathways to the decarbonisation of the existing superyacht fleet…

The journey towards decarbonising the superyacht fleet has begun to take off in earnest. If we consider the entire marine sector’s goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050, it’s fair to say that our progress so far has been slow. The shipping sector has already produced extensive reports and diverse case studies, and developed mature infrastructure and regulatory frameworks, while we seem to be a few steps behind.

Although we can leverage the progress made in the shipping sector to some extent, the unique characteristics of superyachts and their operational profiles require us to move towards innovation. Until recently, serious efforts to break new ground in decarbonisation were exclusively associated with new-build projects, commissioned by a few pioneering owners collaborating with forward-thinking designers and naval architects.

Several new-build yards have made impressive strides towards creating low-emission yachts with future-proofed energy-storage solutions. For instance, the ground-breaking Project Zero, a 69-metre ketch free of fossil fuels and combustion engines, is currently being outfitted at Vitters and is set to launch in 2025.

On an even larger scale, the 114-metre Project Cosmos, the world’s first methanol and fuel-cell-powered motoryacht, is due to be delivered by Lürssen in the same year as well as the secretive pure hydrogen fuel-cell yacht project in the works at Feadship (Royal Van Lent – Amsterdam), to be delivered within the next year or two.

The current superyacht fleet, consisting of more than 6,000 vessels, was built almost entirely without consideration for future shifts in global energy policy and supply. Pier Posthuma de Boer, director refit & services at Feadship, says, “For the new-build fleet, we are using all the knowledge that our team has to construct yachts that are flexible to the next non-fossil shipping fuels and can be easily modified in the future to comply with evolving emissions rules and regulations. Almost everything we’ve built until now as an industry, however, was not, and it presents an interesting challenge.”

Refitting this fleet with future-focused energy storage and propulsion systems is arguably the most significant technical hurdle within our control. Although HVO (hydrotreated vegetable oil) and other paraffinic non-fossil drop-in fuels can facilitate the transition, we should prepare to adopt more advanced and far-reaching solutions for the existing fleet.

At this stage, any serious decarbonisation efforts remain largely voluntary, lacking the pressure of regulations and strict legislation. The intriguing new-build projects serve as intrepid prototypes, paving the way, but at the time of writing very few are following in their footsteps.

“As a shipyard, we advocate for greener solutions. We advise owners to prioritise energy efficiency with each refit opportunity.”

Refit yards, and particularly new-build yards such as Feadship that also have significant refitting activities, will play a leading role in the journey to net zero emissions. “Refitting has not typically been viewed as a profitable investment,” says Posthuma de Boer. “It’s often seen as a necessary expense to preserve the asset and also somewhat of a financial black hole, but that perception is changing.”

Giedo Loeff, head of research and development at Feadship, adds, “Presenting the figures to a client as a business case is becoming easier. If we make certain adjustments to your yacht during a refit, it will significantly increase efficiency and reduce fuel consumption, potentially adding value to the yacht’s resale.” As Loeff highlights, some modifications might actually have a short return time on investment when the increase in fuel costs is factored into the equation.

The approach of Feadship Refits & Services to sustainable refits isn’t overly complicated at present, according to Posthuma de Boer. “We are aware that hotel load is the largest energy consumer on a yacht, for example, and we have solutions to enhance the efficiency of older systems. Another significant area is lighting. While installing LEDs throughout the entire ship is a time-consuming and costly endeavour, it’s a worthwhile investment. We have a long list of standard categories for upgrades that improve energy efficiency.”

The process begins with a comprehensive energy survey. This detailed analysis informs an extensive list of recommended works. “The eight to ten main drivers of consumption on yachts that can be addressed during a refit typically align with the categories of works that the yacht would be looking to undertake anyway,” says Posthuma de Boer. “Even without a full energy survey, most yachts would consider upgrading these systems, and that’s where we can ensure they adopt energy-efficient solutions.”

Loeff points out that many motor boats are overpowered, with engines and generators that exceed necessary capacity, consuming an excessive amount of fuel. “As an industry, we didn’t consider this twenty years ago when building them. But we have a great opportunity now to evolve these systems.”

Many of the efficiency modifications that clients choose to implement will likely be part of regular maintenance and sensible upgrades. As obsolete systems need to be replaced, this will naturally be with more efficient alternatives.

While this represents a vital step, it’s just the beginning of what sustainable refits can achieve and the role that they can play in decarbonisation by 2050. As Bram Jongepier, senior specialist at Feadship De Voogt Naval Architects, aptly stated in his white paper, published in early 2023, “It’s the fuel, stupid!”

Pier Posthuma de Boer, director refit & services, Feadship.

Pier Posthuma de Boer, director refit & services, Feadship.

Speaking from a new-build perspective he added, “Without compromising on luxury, size, freedom and all the other reasons for building a yacht, we can increase efficiency significantly, but there’s a technological limit beyond which we can’t go. To achieve further reduction, we must change our fuel source.”

As highlighted in this study, fossil fuels, when used conventionally to provide energy, make up around 94 per cent per cent of a yacht’s lifetime environmental impact (over a 30-year life span). The next level of sustainable refits, similar to new builds, involves retrofitting engine rooms and tank spaces to accommodate future fuels such as methanol.

However, according to Posthuma de Boer, the decision to invest in major sustainable-focused upgrades largely depends on legislation drivers. “As a shipyard, we advocate for greener solutions. We advise owners to prioritise energy efficiency with each refit opportunity. While we encourage full-scale upgrades to non-diesel systems, it’s a costly and extensive undertaking.”

He adds, “The fact is that currently an owner with a 20-year-old Feadship facing a generator replacement will likely still opt for conventional updates unless future legislation necessitates a different approach. The decision to invest in major sustainable-focused upgrades depends largely on these drivers.”

If the regulatory landscape were to change, and pressure was applied, the refit sector may have to go from undertaking no retrofits of existing vessels for future fuels to a large number – and relativity quickly. On this point, Loeff notes that the EU’s Fit for 55 initiative is expanding, with vessels over 5,000gt required to report their emissions from January 2024, with an envisaged expansion towards 400gt vessels after 2026.

“Large yachts, as well as older ships, already have to report their fuel usage. Being part of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) could be significant,” says Loeff. For instance, if one ton of diesel fuel results in 3.2 tonnes of CO2, the cost could multiply by €90 per ton, nearly equivalent to the price of the fuel itself.

Rising fuel prices due to taxation, the phasing out of fossil-fuel subsidies as discussed at COP28 in Dubai and the introduction of the ETS for superyachts will have downstream effects. Concurrently, the energy market’s efforts to increase non-fossil fuel production and distribution will strengthen the business case for efficiency upgrade refits to cut the associated operating costs, and even to refit towards other fuel-chemicals such as methanol.

“Methanol is attractive because it’s relatively easy,” explains Loeff. While ‘easy’ is a relative term in this context, the point is well made. “Methanol is an important source of energy for ships, but we will still need non-fossil paraffinic drop-in fuels in the future, not only for the superyacht fleet but also for the shipping fleet if we aim to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.”

While there will be room for the production of paraffinic non-fossil drop-in fuels for the current fleet, they will probably be more expensive. Loeff says, “We can retrofit methanol tanks that are large enough to support the base load of energy consumption using fuel cells 100 per cent of the time while stationary, supplementing it with combustion engines [second-generation bio-fuel] only while sailing. This is a realistic option.”

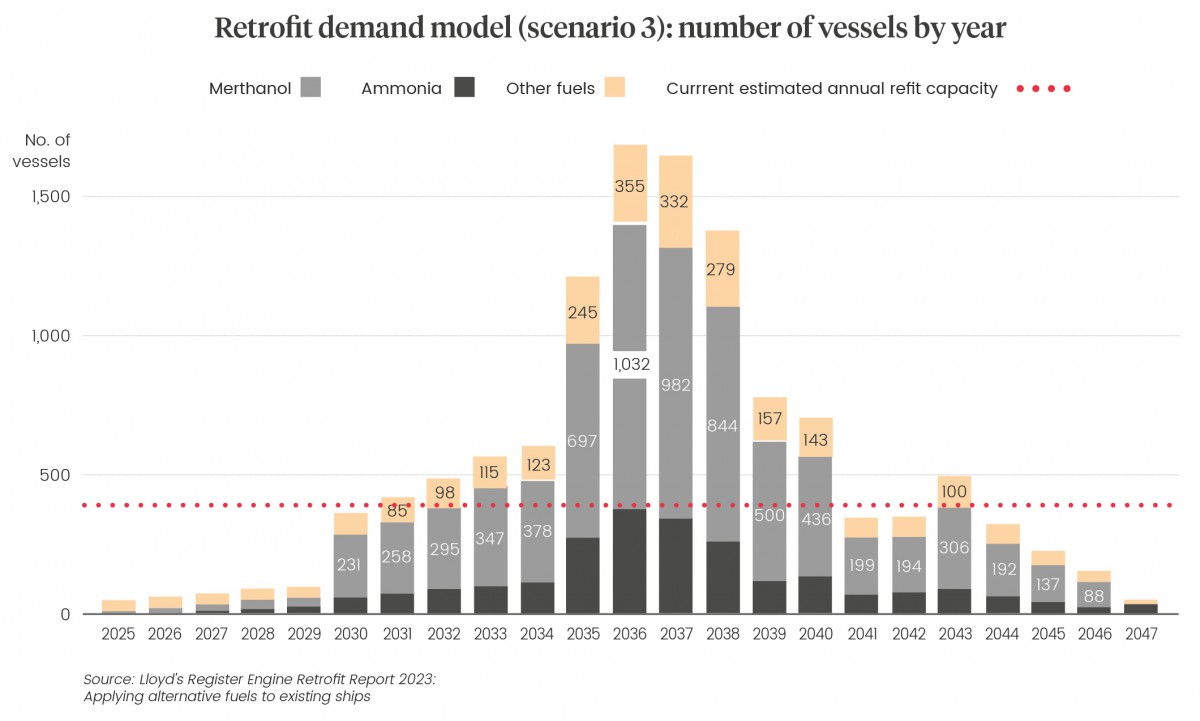

Considering the close connection between the superyacht industry and the shipping sector in terms of decarbonisation, it’s interesting to compare the role of refits in this context also. The extensive Lloyd’s Register Engine Retrofit Report, published in October, sheds light on the shipping industry’s decarbonisation goals by 2050. The report also clearly notes the effect that the sustainable scaling of bio fuels will have, but also considers a future where this doesn’t apply and the shipping fleet looks to large-scale retrofitting.

The report highlights yard capacity, conversion capability and system integration as the main challenges in implementing future fuels technology in the existing global fleet. It also notes that the limited number of existing alternative-fuelled vessels and their recent introduction restricts the ability of repair yards to handle such projects.

The Lloyd’s Register model factors in various fuel options and two key market considerations: a five-year delay before all fossil-fuel new builds start to be phased out, with the last conventionally fuelled vessel launched in 2034; and only vessels under 15 years of age are considered. This results in a potential fleet of 12,900 vessels.

The report reveals that the current annual estimated retrofit capacity falls short of what’s needed to fully transition the fleet to non-fossil-fuel solutions by 2050.

“Methanol is an important source of energy for ships, but we will still need non-fossil paraffinic drop-in fuels in the future if we aim to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.”

Applying a similar approach to the superyacht sector is challenging. Defining a general refit capacity figure is difficult, let alone estimating how many yards can handle such a complex refit, given the absence of case studies.

Because superyachts are relatively compact compared to commercial shipping, refitting to alternative fuels will be a dramatic and costly exercise. Refitting to ammonia, for example, isn’t likely to be of any relevance for the fleet due to the risk of bringing a potentially harmful chemical into densely populated areas, as well as sensitive ecosystems.

It’s assumed that it will be the large custom and high-volume yachts that will have the space and financial means to undertake non-fossil-fuel refit installations. For example, the recently type-approved 70-metre platform, as detailed by Lateral Naval Architects, has scaled its methanol/fuel cell/combustion platform to this size.

Considering the lower energy density of methanol compared to diesel (2.4 times more volume required), this size appears to be the conceptual limit with current technologies to allow for sufficient volume to switch to low-density fuel such as methanol for sustained silent cruising.

This is still only a small percentage of the overall fleet – approximately five per cent of the total 30-metre-plus yachts falls into the 70-metre category. For the existing fleet, as well as the majority of yachts in build and to be built in the future, the reality is that the best option is to run on the paraffinic non-fossil drop-in fuels.

For this, we can turn to the similar steps in aviation and its scaling of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) for a case study. Also of relevance is Formula 1’s switch to net-zero fuels, again not requiring a fundamental change in engine or operations.

For this step, we don’t need to refit, and this is the likely direction in which the market will shift the industry. “We want refit to reduce the operating costs associated with the increased fuel prices and upgrade to IMO tier III compliance,” says Loeff.

He adds, “The partial power fuel-cell refit is an interesting concept because of the availability of non-fossil fuel variant [being methanol] and the fact that we can have fuel cells powering the yacht without pollutant emissions.”

Giedo Leoff, head of research and development, Feadship.

Giedo Leoff, head of research and development, Feadship.

There’s a strong likelihood that a number of yachts will need to look to this kind of system in order to be permitted to access sensitive marine environments. Many of these areas are already established, such as the often-quoted Norwegian fjords. It’s certain that these areas will be expanded significantly in the coming years, as well as the possibility of in-port emissions regulations.

This is where refitting to multi-fuel capacity, whereby tank capacity is increased and certified to carry both diesel (or non-fossil equivalent) and methanol, becomes a viable solution as does the concept of refit to dual fuel gensets and fuel cells. “But being realistic, that market will remain very small until technology further matures,” says Loeff.

The two kinds of sustainability-focused refits outlined by Loeff and Posthuma de Boer can be summarised as:

• Refits that are viable now: energy-efficiency upgrades and exhaust aftertreatment. Yacht owners should be made aware of the necessity & benefits hereof.

• Refits that will become viable in the foreseaable future: Methanol fuel-cell upgrade. As the technology matures, refit shipyards should prepare them-selves and their clients for this great opportunity.

“Retrofitting an old Feadship to be a 100 per cent methanol motoryacht doesn’t make much sense at this stage unless you want to set an example,” says Loeff. “It would involve cutting the vessel in half, incurring significant expenses. At what point does this cease to be a refit and become something else? A combination of [existing] internal combustion engines running on paraffinic non-fossil fuels and methanol fuel cells is more practical.”

“If we’re talking about that next level of refit on the existing fleet, of course we would probably like to do the first few Feadships here at our own shipyards in The Netherlands,” says Posthuma de Boer. “But we have a large fleet and some very experienced refit partners abroad that we would certainly look to join forces with.”

“If the regulatory landscape were to change, and pressure was applied, the refit sector may have to go from undertaking no retrofits of existing vessels for future fuels at all, to a very large number – and relativity quickly.”

Loeff concludes, “Methanol opens the door to adopting fuel cells which offer greater efficiency, extremely quiet operation and produce no local emissions. As technology advances, methanol could become an appealing option for refits provided it aligns with the client’s needs and technological advancements continue.”

Feadship is taking proactive measures in new-build projects, constructing diesel-electric yachts, intending that the diesel part will eventually transition to other fuels. HVO is the starting point, followed by next-generation propulsion systems, building around an electrical system and a yacht with adaptable components that can be replaced to accommodate new engines and generators when required.

However, the reality is that we are still seeing too many yachts opting for older technology generators and engines. These may be fine today, but they form platforms that are not flexible enough to transform to accommodate future-proofed fuels.

In this pivotal moment, the superyacht industry faces the challenge of aligning with global energy transition goals. The emergence of innovative new-build projects signals the potential for change, but the vast existing fleet requires a more comprehensive approach. Refit yards, both in the established yards and further afield, are poised to play a central role in the journey to decarbonisation.

While sustainable refits offer immediate gains in efficiency and emissions reduction, the path forward involves embracing alternative fuels like methanol and paraffinic non-fossil drop-in fuels. As regulations tighten and fuel prices rise, the industry's future will undoubtedly be shaped by its ability to adapt, innovate and prioritise sustainability.

This article first appeared in The Superyacht Refit Report. To gain access to The Superyacht Group’s full suite of content, publications, events and services, click here to join The Superyacht Group Community and become one of our members.

Profile links

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

Gulf Craft to invest in hydrogen

The Dubai-based shipyard is currently exploring the incorporation of hydrogen-ready technology for its superyacht fleet

Crew

The missing superyacht sustainability report

Many industries have overarching sustainability reports, providing insights and accountability. Where is the superyacht equivalent performance assessment?

Opinion

Methanol's colour coding conundrum

Methanol is fast becoming a popular, environmentally friendly alternative fuel, but it is important to understand that not all methanol is created equal

Technology

Feadship – On the Road to Zero

CEO Henk de Vries assesses Feadship’s plan to build carbon-neutral superyachts by 2030, and the wider sector’s green ambitions

Business

Lloyd’s approves Sanlorenzo’s and Feadship's methanol fuel system

Sanlorenzo's methanol fuel system for 50Steel and Feadship's compact multi-fuel system design have secured approval from the classification society

Crew

Related news

Gulf Craft to invest in hydrogen

1 year ago

The missing superyacht sustainability report

1 year ago

Methanol's colour coding conundrum

2 years ago

Feadship – On the Road to Zero

2 years ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek