The evolution of YETI

Our sustainability editor speaks with Robert van Tol, executive director of Water Revolution Foundation, about the latest version of YETI and with Bram Jongepier, senior specialist at Studio De Voogt, who initiated YETI, about how he hopes the industry will further use the tool to drive improvements…

The Yacht Environmental Transparency Index (YETI) is used to assess a yacht’s impact and identify methods to improve it, providing the potential to assist in directing refit projects in a similar way to new builds. This updated version – in the form of a dedicated website and accompanying software for both a new YETI Lite version and the more familiar YETI Pro – builds upon all previous developments since its creation in 2019.

“Before we started YETI, there was a lot of talk about yachts being ‘green’. You could say anything you wanted because there was no test,” says Bram Jongepier, senior specialist at Studio De Voogt. These false and misleading claims triggered Jongepier to start thinking about how to create such a test.

In 2018, a project was conducted at De Voogt, in collaboration with Delft University, into alternative energy carriers, focusing on availability and infrastructure, impact on design and making the sustainable impact measur-able. It’s this latter part, says Jongepier, that triggered YETI after a brainstorm session between the students and the in-house experts at De Voogt.

It was decided YETI would not be a Feadship exercise but should be shared across the industry. Feadship then invited 20 different companies within the industry, including major yards, naval architects and knowledge institutes, to create a Joint Industry Project (JIP) which was adopted by the then recently formed Water Revolution Foundation. The rest is history.

YETI workshop

Jongepier emphasises that from the very beginning there was an awareness that the test needed to be more than just assessing the impact of yacht operations on global warming. “Yes, it’s important, but it’s not the only thing,” he says. He recognised the need to reward other choices made on the vessel that led to other improvements, such as selective catalytic reduction (SCR). Hence YETI uses Ecopoints, which are utilised in different life-cycle assessment applications. The YETI calculator is also able to calculate the CO2 equivalent impact for those who want to focus on only that.

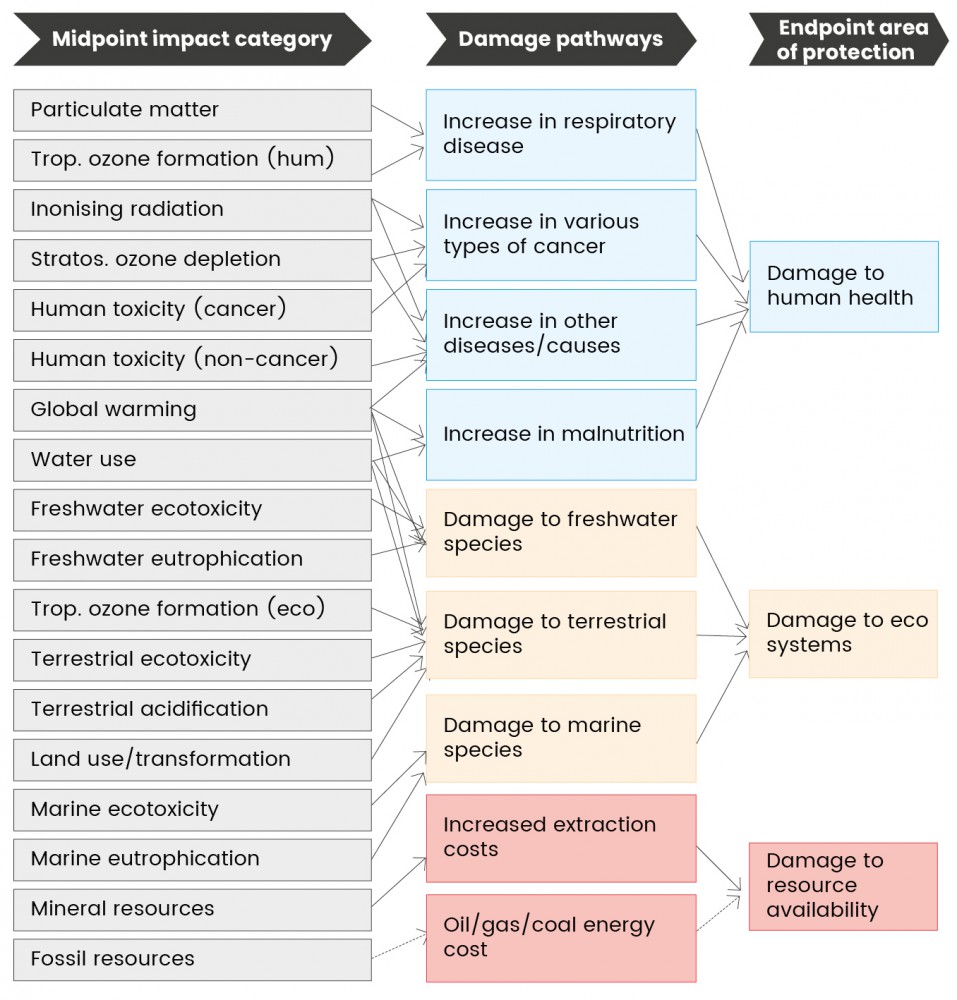

The Ecopoint represents the total environmental load of a product or solution created through its life cycle, aggregating 18 different impact factors across three categories: human health, ecosystem quality and resources. The factors include not only global warming, but also those with different impacts on the environment such as human toxicity, marine ecotoxicity, photochemical oxidation potential, NOx and SOX emissions, and water scarcity footprint. Effectively, this Ecopoint is a measure of sustainability performance, with a lower score indicating a lower impact. The YETI score is the number of Ecopoints per year of operation.

“What we want to accomplish with the software is that it is available to everyone in the sector.”

The next stage of evolution

Since YETI’s creation, there’s been a lot of development to make the tool calculate accurately the footprint of different aspects of yacht operation, with particular complexity surrounding the hotel load. Jongepier says, “Hotel power has been the Achilles heel of YETI for three years, I think because it’s so subjective to calculate. Basically, it’s impossible to calculate.” However, multiple iterations have been able to get more accurate estimations.

The YETI website involves software developed with Maritime Research Institute Netherlands (MARIN). Within this website will be YETI Lite, a new less intensive and free version of the assessment, and YETI Pro, the full YETI assessment.

YETI Lite is a more accessible version of the YETI tool, completely free using only the submitted length overall, gross tonnage and average hotel power. It compares this to a trendline similar to the YETI baseline, generated using gathered fleet information, as well as 2,500 hypothetical but realistic vessels, to produce an estimate of the YETI score for that vessel.

Robert van Tol, executive director of Water Revolution Foundation, explains that when using this for a conventional yacht, the resulting score is 90 per cent accurate compared to the score gained from YETI Pro. “What we want to accomplish with the software is that it is available to everyone in the sector,” says Van Tol. This explains the decision to make YETI Lite completely free, hoping that the accessibility will allow for more use as a guide to estimate how impactful a yacht will be.

YETI Pro, the full YETI assessment, requires the submission of many more details of the yacht, from its design to its operation. The assessment results in a score aggregated from the different impact categories. The higher this score, the more impactful the yacht, but alongside this is a full report detailing the source of the impact from the yacht.

The 18 different impact categories accounted for in Ecopoints

The website will also introduce a new feature – a dashboard where you can visually see the distribution of upstream and downstream factors that feed into the overall YETI score such as fuel production, shore power and the various emissions. As Van Tol says, YETI Pro “is more for the technical people” because it gives a more in-depth analysis of the causes of these different impacts throughout the yacht’s life cycle.

This latest software available on the website will be a big step from the previous iteration, a very complex Excel spreadsheet that, Jongepier explains, “is really reaching or exceeding the limits of what you should do with Excel”. As YETI Pro requires more input of different details of the yacht, where information isn’t available, estimators will be used to fill in the gap. This is where the transparency aspect of the index comes from.

“Solutions that really reduce the energy consumption are more effective on the score than after-treatment systems.”

YETI and the refit process

The YETI Pro report will include sug-gestions for some typical changes to be made to improve the yacht’s impact. This is where it can be useful as a prelude to a refit project.

At the start of a refit, changes can be considered in three categories: reducing energy demand, power generation with higher efficiency and/or lower impact, and on-board sustainable energy genera-tion. Reducing energy demand can be through reduced propulsion power (new propellers, bulbous bow, foils, podded propulsion) or reduced hotel power (high-efficiency equipment, smart controls, double glazing). High efficiency/low impact power generation can be achieved with modern engines, power take-off installation, batteries, heat recovery and exhaust treatment. On-board sustainable energy generation can be found in the application of solar cells or regeneration on sailing yachts.

As identified through Water Revolution Foundation’s work, the hotel load is the most significant, making up more than half of the annual energy demand, so making these adjustments can assist with that. While some of these technologies will be able to be implemented only at certain refit stages, the savings they can offer where possible would be significant. For example, Water Revolution Foundation estimates that implementing heat recovery and other improvements to the HVAC system can provide more than 40 per cent reduction in energy demand.

Van Tol says, “Solutions that really reduce the energy consumption are more effective on the score than after-treatment systems.” One after-treatment suggested in the YETI report is a diesel particulate filter, which will clean the exhaust fumes by removing more particulate matter, one of the impact categories that contribute to the YETI score, and a Selective Catalytic Reduction system (SCR), which reduces harmful NOx emissions in exhaust gases.

The real value of a YETI report, as Jongepier explains, comes from the ability to compare an initial baseline impact to different scenarios with changes made. He says the secondary assessment can answer questions such as: What is the impact if I install a heat-recovery system? What is the impact if I go for batteries? What is the impact of (voluntary) application of an SCR on the generators?

Van Tol says this is similar to a real-life scenario where YETI was used by a naval architecture studio which, after an initial assessment, did it again for two other potential scenarios. This enabled the naval architecture studio to present the three options: either status quo or the different sets of changes, each with their calculated effect on the vessel’s impact and the associated costs.

Hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) as a drop-in alternative fuel to diesel “is more expensive, but you save 60, 70, 80, 90 per cent of CO2 depending on the feedstock. There is no other thing you can do that is so effective.”

YETI and alternative fuels

While changes can be made at refit, Jongepier admits that some of the biggest ones may be too extensive to complete. He gives the example of a methanol conversion project Feadship was working on, where the changes to the yacht were so extensive they needed to “rip out the interior of half the boat to get those tanks in”, meaning the yacht would have been out of action for three quarters of a year. This was too much for the owner to agree to go ahead.

This can be a common reaction and, as such, Jongepier emphasises that it’s better to have made these considerations at the new-build phase, especially suggesting that more yachts should be built with fuel-flexibility capabilities. This is particularly important because it’s expected that methanol fuel cells, which reduce fuel consumption by up to 30 per cent, will be available for refit projects within the next five to ten years. With a minimum lifespan of a yacht of 30 years, it’s important to be ready for this.

While some fossil-fuel alternatives need these extensive design changes away from the conventional, there are options that require no changes at the refit stage and can provide significant reduction in emissions. Both Van Tol and Jongepier are proponents of using hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) as a drop-in alternative fuel to diesel. Jongepier says, “Yes, it’s more expensive, but you save 60, 70, 80, 90 per cent of CO2 depending on the feedstock. There is no other thing you can do that is so effective.”

Van Tol goes further and explains that it’s not just the awareness of this fuel that needs to improve, but also the mindset about where the impact of yacht operations come from. “It’s the fuel, not the machine. And I think that’s a mental change that we need to make.” This is reflected in the YETI report suggestions, which all come back to reducing the quantity of fossil fuel burnt.

However, Jongepier recognises that HVO is made from a waste stream, so supply could have its limitations due to general efforts to reduce waste but, as Van Tol hopes, more interest and demand for this will improve the development of its associated infrastructure and supply. Alongside HVO there are also e-diesels that can have comparatively fewer emissions by being created using captured carbon and having less harmful emissions.

Because of the importance of the fuel on the impact, YETI accepts other fuels within its assessment, although Jongepier mentions that it does make com-parisons between yachts more difficult in some cases. For example, if a yacht switches to HVO, it appears much better than other yachts as the fleet reference lines are based on fossil fuels. However, it could still be a much less efficient yacht that would otherwise compare very poorly to the rest of the fleet. Using HVO is actually an operational decision, independent of how efficient a yacht is.

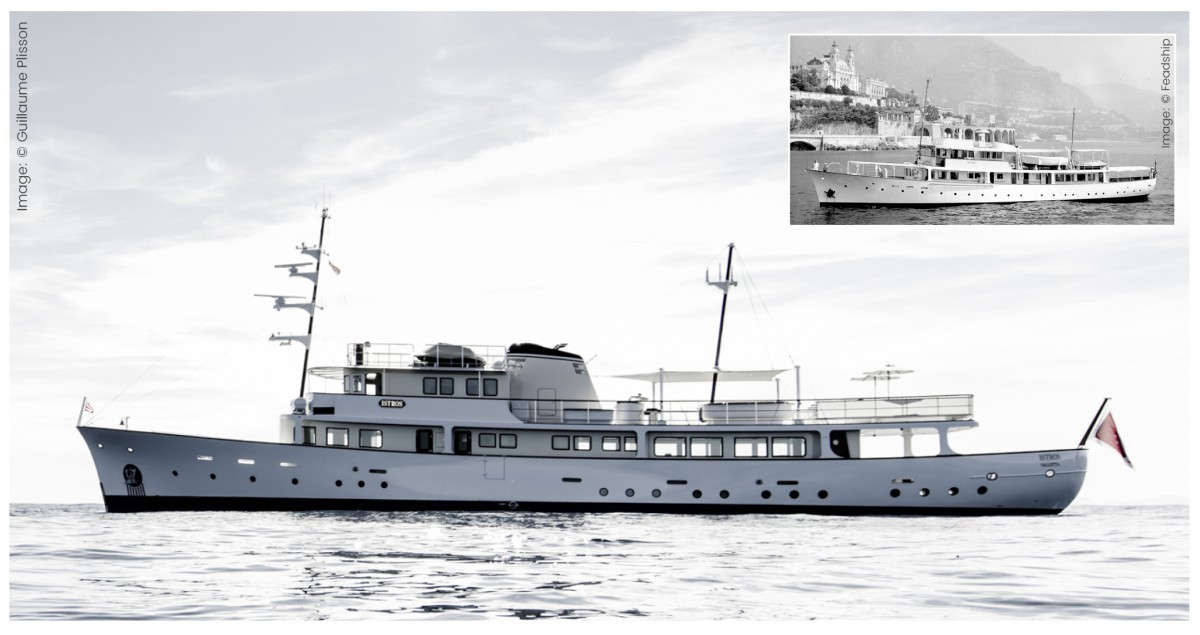

M/Y Istros, 1954 yacht (inset), refitted with 2020 ‘clean’ technology: a silent microturbine in combination with a battery bank, improved HVAC and heat recovery, as well as thermal insulation reducing heating demand.

HVO and alternative diesel can provide other benefits to a yacht alongside the reduction in environmental impact. Jongepier explains, “It smells less and your oil changes don’t have to be done as much.” This improves operations by reducing costs and enhancing the experience on board. Jongepier also testifies that charter guests are asking for green operation, which can best be achieved through HVO.

Carbon pricing is likely to be more expensive due to increasing regulations, meaning the price of fossil fuels will rise and therefore make alternatives more competitively priced. This reflects the other secondary benefits of the improvements the YETI report recommends, which may assist in encouraging more owners and operators to adopt these changes.

Jongepier says, “Owners are just like normal people. Some of them really want to go the whole way, they really want their boat to be exceptionally sustainable. And a lot of them don’t want to seem unsustainable. And some of them just don’t care.” These second and third groups are the majority who need motivating.

Jongepier suggests that the only two ways to truly spur this larger group to make significant changes is “either via the wallet or via the law”. This would be achieved either through a carbon levy and similar financial consequences related to environmentally harmful activities or other regulations that will prevent damaging activities, both of which are likely to increase in the future.

Other companies, such as those in insurance, will be requesting more evidence of actions being taken to reduce environmental impacts because of the pressures they are facing to improve their own operations.

The costs of YETI

A significant benefit from many of the YETI suggestions is that reducing energy demand will reduce fuel and other operating costs, so in a way these changes are what Van Tol calls ‘a cost investment’. He feels these operational costs can often be overlooked at the refit stage due to the focus on the initial price tag, with less regard taken to operational costs because of the uncertainty of the length of ownership. Despite this, Van Tol says, “Really it should be part of the conversation because efficiencies in the end also save cost.”

However, alongside the cost investment, such changes can also be an investment in the superyacht as an asset to prevent it becoming ‘stranded’, particularly as it’s likely to become more difficult to own and operate these assets without making environmental impact improvements. For instance, in the latest YETI webinar, BNP Paribas said it is now more frequently requesting YETI reports to support their own efforts to improve the impact of their portfolio.

Similarly, Van Tol proposes that other companies, such as those in insurance, will be requesting more evidence of actions being taken to reduce environmental impacts because of the pressures they are facing to improve their own operations.

The consequences of inaction can make it more difficult to operate and may lead to increased costs such as higher insurance premiums, and also can devalue the superyacht. So not only are there cost savings to be had, there’s also the avoidance of future price increases from an increasingly conscious corporate world.

Future developments

The upcoming new YETI software and website are just the start in the latest developments relating to YETI. Currently, work is being done to create an ISO standard where the method by the YETI JIP is proposed. The ISO group brings together different experiences, knowledge and perspectives, involving Classification societies and professionals from the operational side, including representatives from Monaco who are members of The Monegasque Association for Standardization as well as the representative of ISO in Monaco.

This working group recently submitted a committee draft, which means that following the ISO standard schedule, this standard will need to be finalised in approximately a year. Jongepier is optimistic this will be achieved given the latest developments in YETI. He says this standard means “that it can be referenced, for instance, by people in a specification or even by Class or Flag”. This brings more authenticity to the YETI process.

It’s clear there are a number of options to improve the environmental characteristics of a yacht at the refit stage. Despite some resistance to adopting these, Van Tol remains optimistic. “The positive news on the yacht fleet is that it can be better,” he says. Making improvements across the whole fleet, however big or small, can lead to an accumulation of prevented pollution.

Van Tol also argues that offering these improvements “for a refit business is also a business case”. But it’s also a business case for owners and operators in a changing landscape that is only going to increasingly punish inaction in this regard, as well as the operational benefits from upgrading their yacht’s environmental footprint.

This article first appeared in The Superyacht Report – Refit Focus. With our open-source policy, it is available to all for a limited period by following this link, so read and download the latest issue and any of the previous issues in our library. Look out for the New Build issue coming in February!

Profile links

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

How ESG is driving Turkish marinas

Kemal Altuğ Özgün and the CBC Law team discuss how ESG principles are driving sustainability and financial success for marinas

Crew

Why marinas matter

Yachts can spend up to 90 per cent of their life in a marina, so onshore ESG practices are more important now than ever

Crew

Feadship’s concept C unveiled at Monaco

The 75-metre motoryacht conceived for the yard’s diamond anniversary is on display at the Monaco Yacht Show this week

Fleet

Scope 3 emissions – their challenges and potential solutions

As Scope 3 becomes critical to reporting and disclosure regulations, businesses must understand and manage these emissions to future-proof their business

Business

New CO2 emissions tracking tool

Sea Index® and RINA are collaborating on the next addition to their methodology, focusing on the life-cycle impact of fuels, from conventional to biofuels

Crew

Related news

How ESG is driving Turkish marinas

6 months ago

Why marinas matter

6 months ago

Feadship’s concept C unveiled at Monaco

7 months ago

New CO2 emissions tracking tool

8 months ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek